Who's on Board ?

June 2018

And the award goes to …. UCL Business plc. Chapeau to Cengiz Tarhan and his colleagues.

UCL Business has the highest proportion of women directors, with 3 out of 9, 33%.

This article looks at the current practice of a few leading UK universities in the composition of their technology transfer company boards of directors, and to provide some comments on these practices. The article also provides an overview of how knowledge/technology transfer activiities are structured across UK universities.

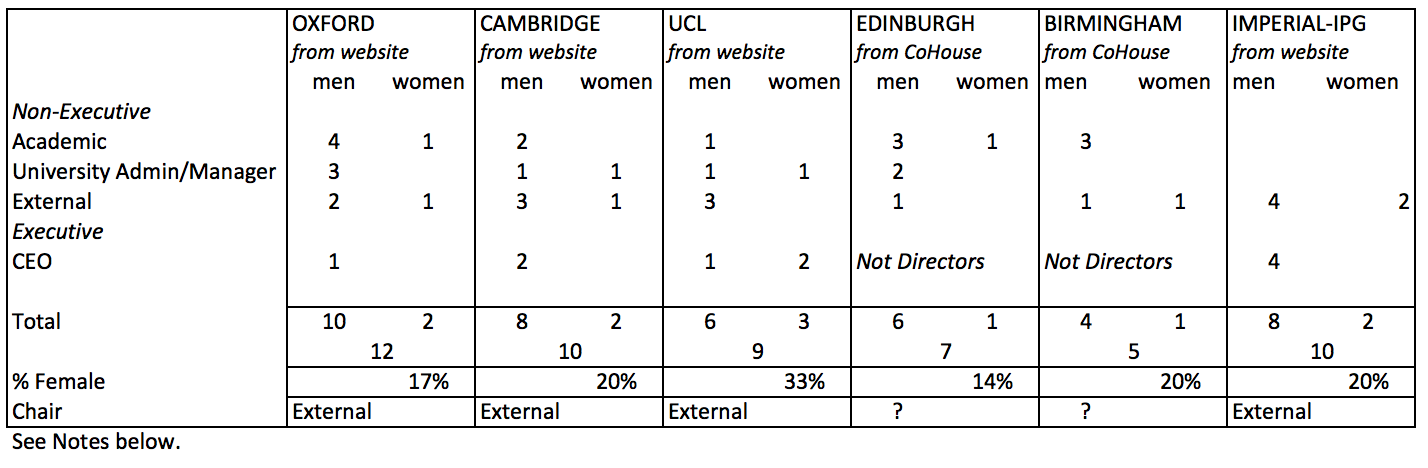

The table below shows membership of the Boards of Directors of the leading university technology transfer companies in the UK.

The data for company directors are shown by non-executive and executive, and male and female. The Non-executives are placed in one of three categories: (i) academic at the home university; (ii) university administrator / manager at the home university; and (iii) external.

The table below shows membership of the Boards of Directors of the leading university technology transfer companies in the UK.

The data for company directors are shown by non-executive and executive, and male and female. The Non-executives are placed in one of three categories: (i) academic at the home university; (ii) university administrator / manager at the home university; and (iii) external.

Diversity

UCL Business has the highest number and proportion of female directors, with 3 out of 9, 33%. All others are 20% (one in five), or lower.

Data from leading TTO companies ‘down-under’ (Aus, NZ, not shown above) show one with one female director out of seven (14%) and another with one female director out of nine (11%).

All of the Directors of all these companies appear to be white (based on websites, LinkedIn, pictures, names; apologies for any incorrect assumptions), with one exception, out of over 50 people.

Although not shown in the table, amongst the six universities there are two ‘Academic’ directors from the Social Sciences, Humanities and the Arts; one of these from a Business School, one from the Humanities. All of the others are from the Life, Clinical and Physical Sciences.

All the boards include representatives from within the University and also external to the University. The balance of Academic and Admin/Management amongst the University people varies. The presence of External non-executive directors is important given the commercial nature of the technology transfer business, and the need for business and investment experience that cannot be found inside a University.

Size and shape

University of Birmingham Enterprise Ltd has a small Board, with 5 members; Oxford University Innovation Ltd has the largest Board, with 12 members.

Only Oxford, Cambridge and UCL have an executive CEO on the Board. Others have a head of technology transfer, employed by the company, but not appointed as a Director. At Cambridge Enterprise Ltd the two senior executives are both on the Board, at UCL Business three.

The Chairs for Oxford, Cambridge and UCL are all external.

Comments

For those universities with a high proprtion of men on their boards and therefore a low proprtion of women on their Boards, there are a whole lot of reasons why a higher proportion of women is a good idea, and organisations are running out of excuses for not correcting the balance.

The UK Government has recently published a list of some of the reasons given for not appointing women to Boards, in this case for FTSE350 companies. It is an astonishing list:

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/revealed-the-worst-explanations-for-not-appointing-women-to-ftse-company-boards - https://www.gov.uk/government/news/revealed-the-worst-explanations-for-not-appointing-women-to-ftse-company-boards

I wonder what a list from universities may include.

For those universities wishing to promote commercialisation in the Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts, an ‘Academic’ Board Director from these subjects would be a good idea.

Having an ‘External’ Director as Chair is a very good idea, in order to emphasise the commercial nature of the activity, and to avoid Board meetings becoming Committee meetings (the default mode for university people).

Having a majority of University people (Academic and Admin/Management) is a good idea; in order to provide reassurance to the University that it can control the board of its own wholly owned company.

With appropriate governance arrangements in place between the company and the university, and with an external Chair, a wholly owned technology transfer company for the commercialisation of research outputs is a good idea.

All The Others

The vast majority of universities in the UK do not have subsidiary companies for technology transfer. No analysis has been conducted here on the composition of the university committees that have oversight of technology transfer in these universities. These are likely to be Research Committees, sub-committees of Research Committees, Research and Enterprise Committees, Research and Innovation Committees etc.

Overall, analysis in September 2017 of 145 universities in the UK shows the following:

- 112 universities have an identfiable knowledge transfer / technology transfer office of some sort (77%); 27 do not; to put it another way, a little over three quarters do, a little under a quarter do not.

- Of these 112 universities, there are 12 technology transfer companies [12/112 = 11%; 12/145 = 8%]. One hundred are offices within the administration of the university.

- Of these 12 companies, two are plc (UCL and Imperial/IPGroup); one is not wholly-owned (Imperial/IPG); and three are not Russell Group (Ulster, Swansea, LSHTM).

For the majority of the administrative offices, technology transfer is one of a number of complementary areas of responsibility.

Reading down a list of the names of the 100 administrative offices is mesmerizing: as wide a range of combinations of the words Research, Enterprise, Innovation, with a scattering of Business and Knowledge, as you can imagine. Even an ‘Impact’ from the most forward looking (or is that most recently re-organised?) offices.

There are many pros and cons for a university when considering how to structure its technology transfer, whether as a wholly owned company or an adminstrative unit within the university. These are discussed in an earlier article, here: http://www.technologytransferinnovation.com/tto-structure.html

Conclusion

End of term report – needs improvement; more work to be done! University technology transfer company boards lack diversity.

Notes:

The data are drawn from university and company websites and Companies House in March-May 2018. There may have been changes since.

There is some overlap between senior academics in university management positions; in general ‘pro-vice-chancellors’ are allocated to the ‘University Admin/Manager’ category, although of course they are likely to be senior academics, maintaining some teaching and research activities.

The data for Imperial are for IP Group plc, which is far more than the technology transfer company of Imperial College.

Using percentages for groups of less than one hundred has its weaknesses; however, it provides for useful general comparisons here.

There are different views of how many universities there are in the UK. The 145 come from Hefce-Hebce data.